- 1 1. What You Will Learn in This Article

- 2 2. What Polymorphism Means in Java

- 3 3. The Core Mechanism: Method Overriding and Dynamic Binding

- 3.1 3.1 What Is Decided at Compile Time vs Runtime

- 3.2 3.2 Method Availability Is Checked at Compile Time

- 3.3 3.3 The Actual Method Is Chosen at Runtime

- 3.4 3.4 Why Dynamic Binding Enables Polymorphism

- 3.5 3.5 Why static Methods and Fields Are Different

- 3.6 3.6 Common Beginner Confusion — Clarified

- 3.7 3.7 Section Summary

- 4 4. Writing Polymorphic Code Using Inheritance (extends)

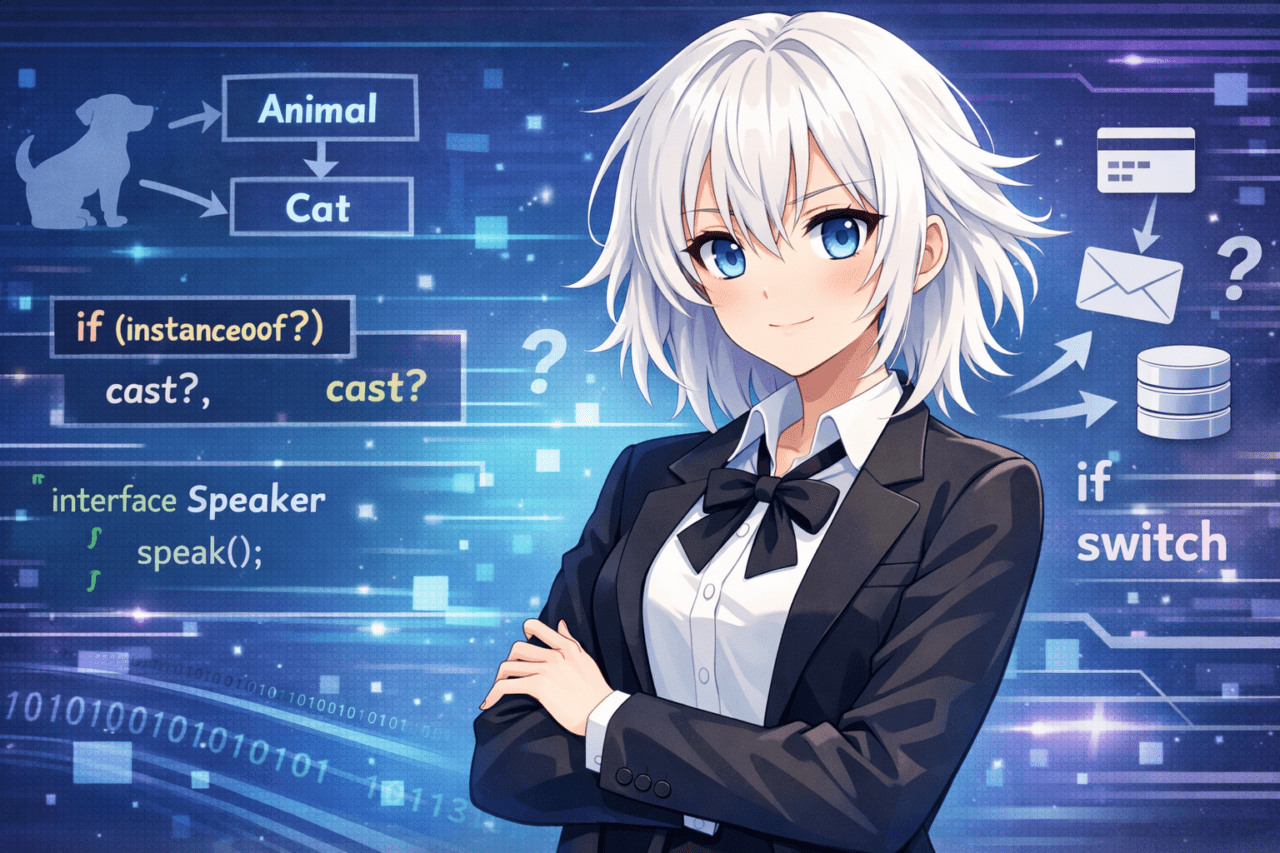

- 5 5. Writing Polymorphic Code Using Interfaces (implements)

- 5.1 5.1 Interfaces Represent “What an Object Can Do”

- 5.2 5.2 Defining Behavior in Implementing Classes

- 5.3 5.3 Using the Interface Type in Calling Code

- 5.4 5.4 Why Interfaces Are Preferred in Practice

- 5.5 5.5 Real-World Example: Swappable Behavior

- 5.6 5.6 Interface vs Abstract Class — How to Choose

- 5.7 5.7 Section Summary

- 6 6. Common Pitfalls: instanceof and Downcasting

- 7 7. Replacing if / switch Statements With Polymorphism

- 8 8. Practical Guidelines: When to Use Polymorphism — and When Not To

- 9 9. Summary: Key Takeaways on Java Polymorphism

- 10 10. FAQ: Common Questions About Java Polymorphism

- 10.1 10.1 What is the difference between polymorphism and method overriding?

- 10.2 10.2 Is method overloading considered polymorphism in Java?

- 10.3 10.3 Why should I use interfaces or parent types?

- 10.4 10.4 Is using instanceof always bad?

- 10.5 10.5 When should I choose an abstract class instead of an interface?

- 10.6 10.6 Does polymorphism hurt performance?

- 10.7 10.7 Should I replace every if or switch with polymorphism?

- 10.8 10.8 What are good practice examples?

1. What You Will Learn in This Article

1.1 Polymorphism in Java — Explained in One Sentence

In Java, polymorphism means:

“Treating different objects through the same type, while their actual behavior changes depending on the concrete object.”

In simpler terms, you can write code using a parent class or interface, and later swap the actual implementation without changing the calling code.

This idea is a cornerstone of object-oriented programming in Java.

1.2 Why Polymorphism Matters

Polymorphism is not just a theoretical concept.

It directly helps you write code that is:

- Easier to extend

- Easier to maintain

- Less fragile when requirements change

Typical situations where polymorphism shines include:

- Features that will gain more variations over time

- Code filled with growing

if/switchstatements - Business logic that changes independently of its callers

In real-world Java development, polymorphism is one of the most effective tools for controlling complexity.

1.3 Why Beginners Often Struggle With Polymorphism

Many beginners find polymorphism difficult at first, mainly because:

- The concept is abstract and not tied to new syntax

- It is often explained together with inheritance and interfaces

- It focuses on design thinking, not just code mechanics

As a result, learners may “know the term” but feel unsure about when and why to use it.

1.4 The Goal of This Article

By the end of this article, you will understand:

- What polymorphism actually means in Java

- How method overriding and runtime behavior work together

- When polymorphism improves design — and when it doesn’t

- How it replaces conditional logic in real applications

The goal is to help you see polymorphism not as a difficult concept, but as a natural and practical design tool.

2. What Polymorphism Means in Java

2.1 Treating Objects Through a Parent Type

At the core of polymorphism in Java is one simple idea:

You can treat a concrete object through its parent class or interface type.

Consider the following example:

Animal animal = new Dog();Here is what is happening:

- The variable type is

Animal - The actual object is a

Dog

Even though the variable is declared as Animal, the program still works correctly.

This is not a trick — it is a fundamental feature of Java’s type system.

2.2 The Same Method Call, Different Behavior

Now look at this method call:

animal.speak();The code itself never changes.

However, the behavior depends on the actual object stored in animal.

- If

animalrefers to aDog→ the dog’s implementation runs - If

animalrefers to aCat→ the cat’s implementation runs

This is why it is called polymorphism —

one interface, many forms of behavior.

2.3 Why Using a Parent Type Is So Important

You might wonder:

“Why not just use

Doginstead ofAnimaleverywhere?”

Using the parent type gives you powerful advantages:

- The calling code does not depend on concrete classes

- New implementations can be added without modifying existing code

- Code becomes easier to reuse and test

For example:

public void makeAnimalSpeak(Animal animal) {

animal.speak();

}This method works for:

DogCat- Any future animal class

The caller only cares about what the object can do, not what it is.

2.4 Relationship Between Polymorphism and Method Overriding

Polymorphism is often confused with method overriding, so let’s clarify.

- Method overriding

→ A subclass provides its own implementation of a parent method - Polymorphism

→ Calling the overridden method through a parent-type reference

Overriding enables polymorphism, but polymorphism is the design principle that uses it.

2.5 This Is Not New Syntax — It’s a Design Concept

Polymorphism does not introduce new Java keywords or special syntax.

- You already use

class,extends, andimplements - You already call methods the same way

What changes is how you think about object interaction.

Instead of writing code that depends on concrete classes,

you design code that depends on abstractions.

2.6 Key Takeaway From This Section

To summarize:

- Polymorphism allows objects to be used through a common type

- The actual behavior is determined at runtime

- The caller does not need to know implementation details

In the next section, we will explore why Java can do this,

by looking at method overriding and dynamic binding in detail.

3. The Core Mechanism: Method Overriding and Dynamic Binding

3.1 What Is Decided at Compile Time vs Runtime

To truly understand polymorphism in Java, you must separate compile-time behavior from runtime behavior.

Java makes two different decisions at two different stages:

- Compile time

→ Checks whether a method call is valid for the variable’s type - Runtime

→ Decides which implementation of the method is actually executed

This separation is the foundation of polymorphism.

3.2 Method Availability Is Checked at Compile Time

Consider this code again:

Animal animal = new Dog();

animal.speak();At compile time, the Java compiler only looks at:

- The declared type:

Animal

If Animal defines a speak() method, the call is considered valid.

The compiler does not care which concrete object will be assigned later.

This means:

- You can only call methods that exist in the parent type

- The compiler does not “guess” the subclass behavior

3.3 The Actual Method Is Chosen at Runtime

When the program runs, Java evaluates:

- Which object

animalactually refers to - Whether that class overrides the called method

If Dog overrides speak(), then Dog’s implementation is executed, not Animal’s.

This runtime method selection is called dynamic binding (or dynamic dispatch).

3.4 Why Dynamic Binding Enables Polymorphism

Without dynamic binding, polymorphism would not exist.

If Java always called methods based on the variable’s declared type,

this code would be meaningless:

Animal animal = new Dog();Dynamic binding allows Java to:

- Delay the method decision until runtime

- Match behavior to the actual object

In short:

- Overriding defines variation

- Dynamic binding activates it

Together, they make polymorphism possible.

3.5 Why static Methods and Fields Are Different

A common source of confusion is static members.

Important rule:

- Static methods and fields do NOT participate in polymorphism

Why?

- They belong to the class, not the object

- They are resolved at compile time, not runtime

This means:

Animal animal = new Dog();

animal.staticMethod(); // resolved using Animal, not DogThe method selection is fixed and does not change based on the actual object.

3.6 Common Beginner Confusion — Clarified

Let’s summarize the key rules clearly:

- Can I call this method?

→ Checked using the declared type (compile time) - Which implementation runs?

→ Decided by the actual object (runtime) - What supports polymorphism?

→ Overridden instance methods only

Once this distinction is clear, polymorphism stops feeling mysterious.

3.7 Section Summary

- Java validates method calls using the variable’s type

- The runtime chooses the overridden method based on the object

- This mechanism is called dynamic binding

- Static members are not polymorphic

In the next section, we will look at how to write polymorphic code using inheritance (extends), with concrete examples.

4. Writing Polymorphic Code Using Inheritance (extends)

4.1 The Basic Inheritance Pattern

Let’s start with the most straightforward way to implement polymorphism in Java: class inheritance.

class Animal {

public void speak() {

System.out.println("Some sound");

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

@Override

public void speak() {

System.out.println("Woof");

}

}

class Cat extends Animal {

@Override

public void speak() {

System.out.println("Meow");

}

}Here:

Animaldefines a common behavior- Each subclass overrides that behavior with its own implementation

This structure is the foundation of polymorphism via inheritance.

4.2 Using the Parent Type Is the Key

Now look at the calling code:

Animal a1 = new Dog();

Animal a2 = new Cat();

a1.speak();

a2.speak();Even though both variables are of type Animal,

Java executes the correct implementation based on the actual object.

Dog→"Woof"Cat→"Meow"

The calling code does not need to know — or care — about the concrete class.

4.3 Why Not Use the Subclass Type Directly?

Beginners often write code like this:

Dog dog = new Dog();

dog.speak();This works, but it limits flexibility.

If you later introduce another animal type, you must:

- Change variable declarations

- Update method parameters

- Modify collections

Using the parent type avoids these changes:

List<Animal> animals = List.of(new Dog(), new Cat());The structure stays the same even as new subclasses are added.

4.4 What Belongs in the Parent Class?

When designing inheritance-based polymorphism, the parent class should contain:

- Behavior shared by all subclasses

- Methods that make sense regardless of the concrete type

Avoid putting behavior in the parent class that only applies to some subclasses.

That usually indicates a design problem.

A good rule of thumb:

If treating an object as the parent type feels “wrong,” the abstraction is incorrect.

4.5 Using Abstract Classes

Sometimes the parent class should not have a default implementation at all.

In such cases, use an abstract class.

abstract class Animal {

public abstract void speak();

}This enforces rules:

- Subclasses must implement

speak() - The parent class cannot be instantiated

Abstract classes are useful when you want to force a contract, not provide behavior.

4.6 The Downsides of Inheritance

Inheritance is powerful, but it has trade-offs:

- Strong coupling between parent and child

- Rigid class hierarchies

- Harder refactoring later

For these reasons, many modern Java designs favor interfaces over inheritance.

4.7 Section Summary

- Inheritance enables polymorphism via method overriding

- Always interact through the parent type

- Abstract classes enforce required behavior

- Inheritance should be used carefully

Next, we will explore polymorphism using interfaces, which is often the preferred approach in real-world Java projects.

5. Writing Polymorphic Code Using Interfaces (implements)

5.1 Interfaces Represent “What an Object Can Do”

In real-world Java development, interfaces are the most common way to implement polymorphism.

An interface represents a capability or role, not an identity.

interface Speaker {

void speak();

}At this stage, there is no implementation — only a contract.

Any class that implements this interface promises to provide this behavior.

5.2 Defining Behavior in Implementing Classes

Now let’s implement the interface:

class Dog implements Speaker {

@Override

public void speak() {

System.out.println("Woof");

}

}

class Cat implements Speaker {

@Override

public void speak() {

System.out.println("Meow");

}

}These classes do not share a parent-child relationship.

Yet, they can be treated uniformly through the Speaker interface.

5.3 Using the Interface Type in Calling Code

The power of interfaces becomes clear on the calling side:

Speaker s1 = new Dog();

Speaker s2 = new Cat();

s1.speak();

s2.speak();The calling code:

- Depends only on the interface

- Has no knowledge of concrete implementations

- Works unchanged when new implementations are added

This is true polymorphism in practice.

5.4 Why Interfaces Are Preferred in Practice

Interfaces are often favored over inheritance because they provide:

- Loose coupling

- Flexibility across unrelated classes

- Support for multiple implementations

A class can implement multiple interfaces, but can only extend one class.

This makes interfaces ideal for designing extensible systems.

5.5 Real-World Example: Swappable Behavior

Interfaces shine in scenarios where behavior may change or expand:

- Payment methods

- Notification channels

- Data storage strategies

- Logging mechanisms

Example:

public void notifyUser(Notifier notifier) {

notifier.send();

}You can add new notification methods without modifying this method.

5.6 Interface vs Abstract Class — How to Choose

If you are unsure which one to use, follow this guideline:

- Use an interface when you care about behavior

- Use an abstract class when you want shared state or implementation

In most modern Java designs, starting with an interface is the safer choice.

5.7 Section Summary

- Interfaces define behavior contracts

- They enable flexible, loosely coupled polymorphism

- Calling code depends on abstractions, not implementations

- Interfaces are the default choice in professional Java design

Next, we will examine a common pitfall: using instanceof and downcasting, and why they often indicate a design problem.

6. Common Pitfalls: instanceof and Downcasting

6.1 Why Developers Reach for instanceof

When learning polymorphism, many developers eventually write code like this:

if (speaker instanceof Dog) {

Dog dog = (Dog) speaker;

dog.fetch();

}This usually happens because:

- A subclass has a method not declared in the interface

- Behavior needs to differ based on the concrete class

- Requirements were added after the original design

Wanting to “check the real type” is a natural instinct — but it often signals a deeper issue.

6.2 What Goes Wrong When instanceof Spreads

Using instanceof occasionally is not inherently wrong.

The problem arises when it becomes the main control mechanism.

if (speaker instanceof Dog) {

...

} else if (speaker instanceof Cat) {

...

} else if (speaker instanceof Bird) {

...

}This pattern leads to:

- Code that must change every time a new class is added

- Logic centralized in the caller instead of the object

- Loss of polymorphism’s core benefit

At that point, polymorphism is effectively bypassed.

6.3 The Risk of Downcasting

Downcasting converts a parent type into a specific subtype:

Animal animal = new Dog();

Dog dog = (Dog) animal;This works only if the assumption is correct.

If the object is not actually a Dog, the code fails at runtime with a ClassCastException.

Downcasting:

- Pushes errors from compile time to runtime

- Makes assumptions about object identity

- Increases fragility

6.4 Can This Be Solved With Polymorphism?

Before using instanceof, ask yourself:

- Can this behavior be expressed as a method?

- Can the interface be expanded instead?

- Can responsibility be moved into the class itself?

For example, instead of checking types:

speaker.performAction();Let each class decide how to perform that action.

6.5 When instanceof Is Acceptable

There are cases where instanceof is reasonable:

- Integration with external libraries

- Legacy code you cannot redesign

- Boundary layers (adapters, serializers)

The key rule:

Keep

instanceofat the edges, not at the core logic.

6.6 Practical Guideline

- Avoid

instanceofin business logic - Avoid designs that require frequent downcasting

- If you feel forced to use them, reconsider the abstraction

Next, we will see how polymorphism can replace conditional logic (if / switch) in a clean and scalable way.

7. Replacing if / switch Statements With Polymorphism

7.1 A Common Conditional Code Smell

Consider this typical example:

public void processPayment(String type) {

if ("credit".equals(type)) {

// Credit card payment

} else if ("bank".equals(type)) {

// Bank transfer

} else if ("paypal".equals(type)) {

// PayPal payment

}

}At first glance, this code seems fine.

However, as the number of payment types grows, so does the complexity.

7.2 Applying Polymorphism Instead

We can refactor this using polymorphism.

interface Payment {

void pay();

}

class CreditPayment implements Payment {

@Override

public void pay() {

// Credit card payment

}

}

class BankPayment implements Payment {

@Override

public void pay() {

// Bank transfer

}

}Calling code:

public void processPayment(Payment payment) {

payment.pay();

}Now, adding a new payment type requires no changes to this method.

7.3 Why This Approach Is Better

This design provides several benefits:

- Conditional logic disappears

- Each class owns its own behavior

- New implementations can be added safely

The system becomes open for extension, closed for modification.

7.4 When Not to Replace Conditionals

Polymorphism is not always the right choice.

Avoid overusing it when:

- The number of cases is small and fixed

- Behavior differences are trivial

- Additional classes reduce clarity

Simple conditionals are often clearer for simple logic.

7.5 How to Decide in Practice

Ask yourself:

- Will this branch grow over time?

- Will new cases be added by others?

- Do changes affect many places?

If the answer is “yes,” polymorphism is likely the better choice.

7.6 Incremental Refactoring Is Best

You do not need perfect design from the start.

- Start with conditionals

- Refactor when complexity increases

- Let the code evolve naturally

This approach keeps development practical and maintainable.

Next, we will discuss when polymorphism should be used — and when it should not — in real-world projects.

8. Practical Guidelines: When to Use Polymorphism — and When Not To

8.1 Signs That Polymorphism Is a Good Fit

Polymorphism is most valuable when change is expected.

You should strongly consider it when:

- The number of variations is likely to increase

- Behavior changes independently of the caller

- You want to keep calling code stable

- Different implementations share the same role

In these cases, polymorphism helps you localize change and reduce ripple effects.

8.2 Signs That Polymorphism Is Overkill

Polymorphism is not free. It introduces more types and indirection.

Avoid it when:

- The number of cases is fixed and small

- The logic is short and unlikely to change

- Extra classes would hurt readability

Forcing polymorphism “just in case” often leads to unnecessary complexity.

8.3 Avoid Designing for an Imaginary Future

A common beginner mistake is adding polymorphism preemptively:

“We might need this later.”

In practice:

- Requirements often change in unexpected ways

- Many predicted extensions never happen

It is usually better to start simple and refactor when real needs appear.

8.4 A Practical View of the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

You may encounter the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) when studying OOP.

A practical way to understand it is:

“If I replace an object with one of its subtypes, nothing should break.”

If using a subtype causes surprises, exceptions, or special handling,

the abstraction is likely wrong.

8.5 Ask the Right Design Question

When unsure, ask:

- Does the caller need to know which implementation this is?

- Or only what behavior it provides?

If behavior alone is sufficient, polymorphism is usually the right choice.

8.6 Section Summary

- Polymorphism is a tool for managing change

- Use it where variation is expected

- Avoid premature abstraction

- Refactor toward polymorphism when needed

Next, we’ll wrap up the article with a clear summary and a FAQ section.

9. Summary: Key Takeaways on Java Polymorphism

9.1 The Core Idea

At its heart, polymorphism in Java is about one simple principle:

Code should depend on abstractions, not concrete implementations.

By interacting with objects through parent classes or interfaces,

you allow behavior to change without rewriting the calling code.

9.2 What You Should Remember

Here are the most important points from this article:

- Polymorphism is a design concept, not new syntax

- It is implemented through method overriding and dynamic binding

- Parent types define what can be called

- Actual behavior is decided at runtime

- Interfaces are often the preferred approach

instanceofand downcasting should be used sparingly- Polymorphism helps replace growing conditional logic

9.3 A Learning Path for Beginners

If you are still building intuition, follow this progression:

- Get comfortable using interface types

- Observe how overridden methods behave at runtime

- Understand why conditionals become harder to maintain

- Refactor toward polymorphism when complexity grows

With practice, polymorphism becomes a natural design choice rather than a “difficult concept.”

10. FAQ: Common Questions About Java Polymorphism

10.1 What is the difference between polymorphism and method overriding?

Method overriding is a mechanism — redefining a method in a subclass.

Polymorphism is the principle that allows overridden methods to be called through a parent-type reference.

10.2 Is method overloading considered polymorphism in Java?

In most Java contexts, no.

Overloading is resolved at compile time, while polymorphism depends on runtime behavior.

10.3 Why should I use interfaces or parent types?

Because they:

- Reduce coupling

- Improve extensibility

- Stabilize calling code

Your code becomes easier to maintain as requirements evolve.

10.4 Is using instanceof always bad?

No, but it should be limited.

It is acceptable in:

- Boundary layers

- Legacy systems

- Integration points

Avoid using it in core business logic.

10.5 When should I choose an abstract class instead of an interface?

Use an abstract class when:

- You need shared state or implementation

- There is a strong “is-a” relationship

Use interfaces when behavior and flexibility matter more.

10.6 Does polymorphism hurt performance?

In typical business applications, performance differences are negligible.

Readability, maintainability, and correctness are far more important.

10.7 Should I replace every if or switch with polymorphism?

No.

Use polymorphism when variation is expected and growing.

Keep conditionals when logic is simple and stable.

10.8 What are good practice examples?

Great practice scenarios include:

- Payment processing

- Notification systems

- File format exporters

- Logging strategies

Anywhere behavior needs to be swappable, polymorphism fits naturally